Colon cancer is a common malignancy in the United States. The treatment of patients with colon cancer can be complicated and may require a team of surgical and medical specialists. This review provides general information for patients and their families, covering colon cancer, its risk factors and symptoms, cancer evaluation and staging, and the most common methods of treatment. Because the treatment and prognosis for rectal cancer often differ from colon cancer, rectal cancer is addressed in a separate review.

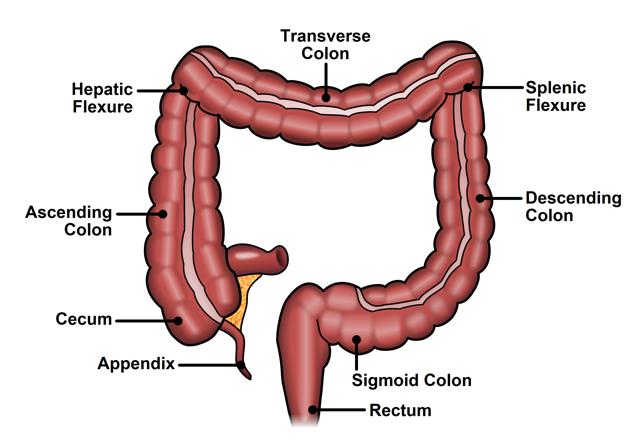

WHAT IS THE COLON?

The large intestine is the last segment of the digestive system. The colon makes up the first 4 to 5 feet of the large intestine and the rectum is the last six inches. Partially digested food enters the colon from the small intestine. The colon removes water and nutrients from the food and turns the rest into waste (stool). The waste passes from the colon into the rectum and then out of the body through the anus (opening).

WHAT IS COLON CANCER?

Colon cancer begins in cells that form the inner lining of the colon. Normally, these cells grow and divide to form new cells as the body needs them. When cells grow old, they die, and new cells take their place. Sometimes this orderly process goes wrong. This happens when cells form when the body does not need them or if old cells do not die when they should. Colon polyps are made up of groups of these abnormal cells. Over time, additional unregulated cell growth may occur and lead to the development of colon cancer. These cancer cells have the ability to invade into the wall of the colon, spread to lymph nodes, or to other organs.

HOW COMMON IS COLON CANCER?

In 2022, an estimated number of 151,000 new colorectal cancer cases are expected to be diagnosed and an estimated number of 52,000 deaths are expected to occur. Over 4% of Americans will develop colorectal cancer in their lifetime. Colorectal polyps (benign abnormal growths) affect about 20% to 30% of American adults.

WHAT ARE THE RISK FACTORS FOR COLON CANCER?

The exact cause of colorectal cancer is unknown. Physicians often cannot explain why one person develops this disease and another does not. However, the understanding of certain genetic causes continues to increase. The following factors can increase the risk of colorectal cancer.

- Age: 90% of the people diagnosed with colorectal cancer are over the age of 50

Family history of colorectal cancer: First-degree relatives (parents, siblings, or children) of a person with a history of colorectal cancer are somewhat more likely to develop this disease themselves, especially if the relative had the cancer at a young age. If several close relatives have a history of colorectal cancer, the risk is even greater.

Family history of colorectal cancer: First-degree relatives (parents, siblings, or children) of a person with a history of colorectal cancer are somewhat more likely to develop this disease themselves, especially if the relative had the cancer at a young age. If several close relatives have a history of colorectal cancer, the risk is even greater.- Personal or family history of colorectal polyps: Polyps are growths on the inner lining of the colon or rectum. Most polyps are benign (not cancerous), but some polyps will progress to become cancer. Finding and removing polyps reduces the risk of colorectal cancer.

- Personal history of colorectal, breast, uterine or ovarian cancer: A person who has already had colorectal cancer may develop colorectal cancer a second time, so it is important to follow-up closely with your treating physicians after undergoing treatment. Also, women with a history of cancer of the ovary, uterus, or breast maybe at a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer.

- Personal history of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis: These conditions cause inflammation of the colon and after many years they can increased risk of developing colorectal cancer.

- Cigarette smoking: A person who smokes cigarettes may be at increased risk of developing polyps and colorectal cancer.

- Diet: Studies suggest that diets high in fat (especially animal fat) and low in calcium, folate and fiber may increase the risk of colorectal cancer. However, results from diet studies do not always agree, and more research is needed to better understand how diet affects the risk of colorectal cancer.

CAN COLON CANCER BE PREVENTED?

Colon cancer is largely preventable. The most important step in preventing colon cancer is getting a screening test. Screening for colon cancer should be a part of routine care for all adults aged 45 years or older. Those with close relatives with colorectal cancer should start screening earlier.

Nearly all cases of colorectal cancer develop from polyps. Detection and removal of polyps through colonoscopy reduces the risk of colorectal cancer. Colonoscopy involves direct visualization of the inside lining of the entire large intestine using a flexible lighted instrument. Polyps can be identified and can often be removed during colonoscopy. For this reason, most healthcare providers recommend starting with colonoscopy as the screening test.

Other screening test options include stool tests (hemoccult, FIT, or fecal DNA), a flexible sigmoidoscopy (partial colonoscopy or shorter scope), or barium enema. Virtual colonoscopy or CT colonography is used in some specific situations but is not recommended for routine screening. Any abnormal screening test should be followed by a colonoscopy.

There is some evidence that a high fiber, low fat diet might help prevent colorectal cancer.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF COLON CANCER?

Many colon cancers cause no symptoms at all and are detected during routine screening examinations. Other common non-cancerous health problems can cause the same symptoms. However, anyone with the following symptoms should see a doctor to be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Symptoms of colon cancer may include:

- A change in bowel habits: constipation, diarrhea, or frequency of bowel movements

- Bright red or very dark blood in the stool

- Narrow/smaller shaped stools

- Ongoing abdominal or pelvic pain and bloating

- Unexplained weight loss

- Nausea or vomiting

- Feeling tired all the time

HOW IS COLON CANCER DIAGNOSED?

Colonoscopy is the most common method for diagnosing colon cancer, although other tests can be suggestive of the diagnosis. If another screening test is positive, it should be followed by a colonoscopy for a more definitive result. During colonoscopy, any abnormal area (such as a polyp, mass, or tumor) is biopsied for cancer cells. A pathologist checks the tissue for cancer cells using a microscope. Currently, there are no reliable blood tests for diagnosing colon cancer.

HOW IS COLON CANCER EVALUATED AND STAGED?

Once a diagnosis of colon cancer is made, your doctor needs to know the extent (clinical stage) of the disease to plan the best treatment.

The stage is based on whether the tumor has spread to nearby tissues, lymph nodes, or other organs, most commonly the liver and lungs. When the cancer spreads to these areas further away from the colon doctors call this “distant” or metastatic disease.

When possible, a thorough diagnostic evaluation should be accomplished prior to undergoing treatment for colon cancer. In addition to taking a personal medical and family history and performing a physical exam, your doctor may order the following tests:

- Blood tests: These may include complete cell counts (to check for anemia), standard blood chemistries and CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) level. CEA is produced by some colon cancers and is useful in detecting cancer recurrence.

- Colonoscopy: Colonoscopy provides useful information about the overall health of the colon and allows for biopsy of the cancer or any other concerning areas. Polyps in other areas of the large intestine may also be removed.

- CT (computed tomography) scan: A highly sensitive x-ray machine able to take a series of detailed pictures of inside your body. A CT scan may show whether cancer has spread to the liver, lungs, or other organs. Other imaging tests may be ordered by your doctor for specific indications such as MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) and PET (positron emission tomography) scans.

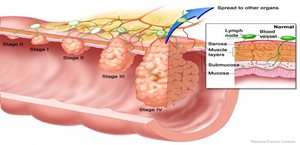

Doctors describe colorectal cancer by the following stages:

Stage 0: The cancer is found only in the innermost lining of the colon or rectum. It may also be referred to as “Carcinoma in situ”.

Stage I: The tumor has grown into the inner wall of the colon or rectum. The tumor has not grown through the wall.

Stage II: The tumor extends more deeply into or through the wall of the colon or rectum. It may have invaded nearby tissue, but cancer cells have not spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage III: The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes, but not to other parts of the body.

Stage IV: The cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the liver or lungs.

Often, final staging is not complete until after surgery to remove the tumor, when the lymph nodes can be evaluated for cancer under a microscope.

Advances in colorectal research [Internet]. Besthesda, MD: National Institute of Health, c.2010 Colon cancer; [cited 2013 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.nih.gov/science/colorectalcancer/

HOW IS COLON CANCER TREATED?

The mainstay of treatment is surgery. The choice of treatment depends mainly on the stage and location of the disease. When colon cancer is found in the early stages, surgery is usually the only treatment required. When diagnosed at more advanced stages chemotherapy may also be given, either as the only treatment or in addition to surgery. Unlike rectal cancer, radiation therapy is rarely used for colon cancer.

HOW IS SURGERY FOR COLON CANCER PERFORMED, AND WHAT IS THE RECOVERY?

Surgery is the most common treatment for colorectal cancer, and it renders many patients disease-free without the need for additional therapy. Surgical resection involves removing the segment of the colon containing the tumor along with the nearby lymph nodes. The surgeon also checks the liver and rest of your intestines to see if the cancer has spread.

Traditionally operations for colon cancer are performed through larger abdominal incisions with standard instrumentation. Minimally invasive surgical techniques such as laparoscopy or robotics may be used by trained surgeons based on the individual case. In these cases, multiple smaller incisions are made in the abdomen. A thin lighted tube (a laparoscope) connected to a video screen is used to see inside the abdominal cavity and the procedure is performed using small instruments.

In some cases, the operation cannot be safely completed with smaller incisions and an open operation is performed. Several large studies have demonstrated that both approaches produce equivalent cancer outcomes. There are specific indications for choosing minimally invasive or open surgery; your surgeon will discuss these features with you prior to the operation.

When a section of your colon is removed, the surgeon can usually reconnect the healthy ends of your intestine. This connection is called an anastomosis. Cigarette smoking, steroids treatment and high blood sugar (diabetes) can predispose to impaired healing of this connection leading to leak of bowel content into your abdomen. Sometimes reconnection is not possible. In this case, the surgeon creates a new path for waste to leave your body. The surgeon makes an opening (stoma) in the wall of the abdomen, connects the end of the intestine to the skin. A flat bag fits over the stoma to collect waste, and a special adhesive holds it in place. The creation of a stoma is typically only done in a very small number of colon cancer patients.

The time it takes to heal after surgery is different for each person. You may be uncomfortable for the first few days. Medicine can help control your pain; you should be comfortable enough to stand and walk with assistance. It is common to feel tired or weak for a while. After surgery it is common to experience some constipation or diarrhea. Your surgeon can provide instructions on the management of these conditions. In addition, your health care team monitors you for signs of bleeding, infection, or other problems requiring immediate treatment.

After discharge from the hospital, you should resume light activity such as walking and personal care. Your surgeon may restrict you from lifting heavy objects for a certain time to reduce the risk of developing a hernia (a bulge under your abdominal incision). Generally, you may resume a normal diet and adequate fluid intake is especially important. Ask your surgeon or nurse prior to discharge about resuming your prior medications in addition to any new medicine you may be taking.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS OF SURGERY FOR COLON CANCER?

Overall, surgery for colon cancer is very safe, with survival in the immediate period after surgery of over 95%. Complications are somewhat more common, occurring in 1 in 5 patients; these can range from minor infections to conditions requiring repeat surgery and prolonged hospital stays. The most common complication is a wound infection at the incision site, typically treated with opening the most superficial layer of the wound and sometimes with antibiotics. Other potential infections include intra-abdominal infection (abscess), urinary tract (bladder) infection, and pneumonia.

Some patients will develop clots in the veins of their legs called deep vein thromboses (DVTs). Walking soon after your operation helps reduce the risk of DVTs, and most surgeons will also prescribe an injectable medication that is used to reduce the risk of developing blood clots.

A small number of patients may experience heavy postoperative rectal bleeding from the colon anastomosis. The bleeding usually occurs within two weeks of the surgery. You should discuss bleeding risks with your doctor if you plan to resume any pre-surgical blood thinners.

Sometimes the connection between the ends of the intestine, the anastomosis, will leak. This serious problem may be treated with antibiotics, a drain placed through the skin, or a repeat operation that may require a colostomy or ileostomy. Your overall health status before surgery influences the risk of other complications such as heart or breathing difficulties.

AFTER SURGERY, WHAT ADDITIONAL THERAPY IS NEEDED FOR COLON CANCER?

Patients in whom colon cancer is found in the lymph nodes (stage III) or distant locations (stage IV) are normally recommended to undergo chemotherapy. Most patients who have colon cancer without spread to lymph nodes or other sites (stage I or II) are treated effectively with surgery alone, although some of these patients with certain risk factors also may benefit from chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses anticancer drugs to kill cancer cells. Studies have shown that chemotherapy improves long-term survival by reducing the risk of cancer recurrence in patients with stage III colon cancer.

Anticancer drugs are usually given through a vein, but some may be given by mouth. Currently, the most common chemotherapy drugs given to patients with colon cancer are 5-fluorouracil (also called 5-FU) and oxaliplatin. Chemotherapy treatment usually begins several weeks after surgery and is done as an outpatient. In addition to killing cancer cells, chemotherapy drugs can harm normal cells that divide rapidly. The side effects of chemotherapy depend mainly on the specific drugs and the dose. Chemotherapy for colorectal cancer can cause generalized fatigue, weakness, increased risk of infections, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, mouth or lip sores, numbness or tingling in the hands and feet. Your health care team can suggest ways to control many of these side effects. Most side effects usually go away after treatment ends.

WHAT FACTORS INFLUENCE OUTCOME AFTER TREATMENT?

The outcome of patients with colon cancer is most closely related to the stage. Patients with early-stage cancer that is confined to the lining of colon have the best prognosis. Factors such as colon perforation or obstruction, or cancer involvement of other organs, lead to a worse outcome. Some features seen on examination under the microscope after surgery also can influence outcome. Your surgeon will discuss the specific findings at your post-operative visit.

WHAT IS THE FOLLOW-UP AFTER TREATMENT FOR COLON CANCER?

Follow-up care after treatment for colon cancer is important. Even after potentially curative surgery and use of additional treatments such as chemotherapy, patients may develop recurrence of the cancer. The risk of recurrence is high if the primary disease is more advanced. Your doctors will continue to monitor your health and check for recurrence of the cancer. Checkups help ensure that any changes in health are noted and treated if needed. Routine physical exams and lab tests generally occur every 3-6 months for the first few years. CT scans and colonoscopy are performed 1 year after surgery. The frequency of subsequent exams is based upon results of the prior exam.

CONCLUSION

Colon cancer is a common malignancy that causes a significant number of deaths. The symptoms of colon cancer are vague and, therefore, require evaluation by health care professionals. Through screening it is potentially preventable and highly curable with surgery alone when diagnosed at an early stage. Modern chemotherapy continues to improve survival for patients with more advanced stages. Colon cancer treatment often requires a team of expert physicians, including colorectal surgeons, medical oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists. These doctors work with the patient to create the safest and most effective therapy plan.

WHAT IS A COLON AND RECTAL SURGEON?

Colon and rectal surgeons are experts in the surgical and non-surgical treatment of diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. They have completed advanced surgical training in the treatment of these diseases as well as full general surgical training. Board-certified colon and rectal surgeons complete residencies in general surgery and colon and rectal surgery, and pass intensive examinations conducted by the American board of Surgery and the American Board of Colon and Rectal Surgery. They are well-versed in the treatment of both benign and malignant diseases of the colon, rectum and anus and are able to perform routine screening examinations and surgically treat conditions if indicated to do so.

DISCLAIMER

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to ensuring high-quality patient care by advancing the science, prevention and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. These brochures are inclusive but not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on diseases and processes, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. They are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed. It should be recognized that these brochures should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of methods of care reasonably directed to obtain the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

ASCRS committee members review and update information for accuracy. We believe content is medically accurate at the time it was produced.

REFERENCES AND ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

Steele SR, Hull TL, Hyman N, Maykel JA, Read TE, Whitlow CB (Editors) The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery, 4nd edition. Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022.

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Colon Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2022; 65: 148–177

The website of the US National Cancer Institute (accessed Jan 2023): SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Colorectal Cancer. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html

Acknowledgement: ASCRS thanks Sean C. Glasgow, MD for his assistance with the development of this educational brochure.