OVERVIEW

The purpose of this patient education piece is to provide providers, patients and their families with information on the background, causes, and treatments of fecal incontinence.

WHAT IS FECAL INCONTINENCE?

Fecal incontinence is the impaired ability to control the release of gas and stool at a desired time. Control of gas and stool is key to maintaining everyday activities and routines, and often people do not consider how important this is until they have a change or loss of control.

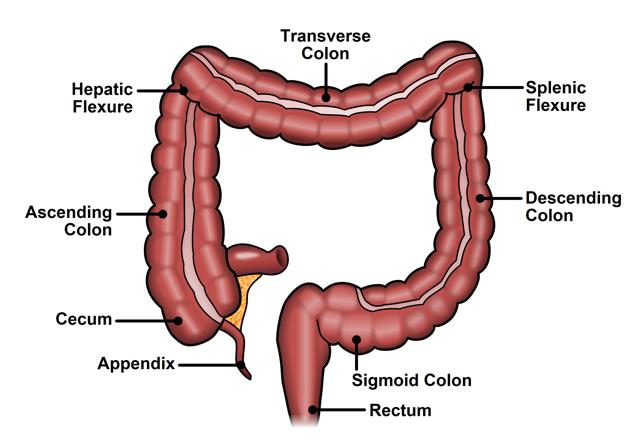

The ability to control gas and stool is a complex function involving multiple organ systems. The colon, rectum, and anus are parts of the digestive system that form a long, muscular tube called the large intestine (also called the large bowel). The colon is the first 4 to 5 feet of the large intestine; the rectum is the next six inches, and the anus (opening) makes up the final 1-2 inches (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Normal colon and rectum anatomy

Partly digested food enters the colon from the small intestine, and the colon removes water electrolytes and turns the rest into solid waste, called stool. As stool enters the rectum, the rectum relaxes and acts as a reservoir to hold the stool. Meanwhile, the outer muscle that encircles the anus, called the external anal sphincter, squeezes to prevent gas or stool leakage.

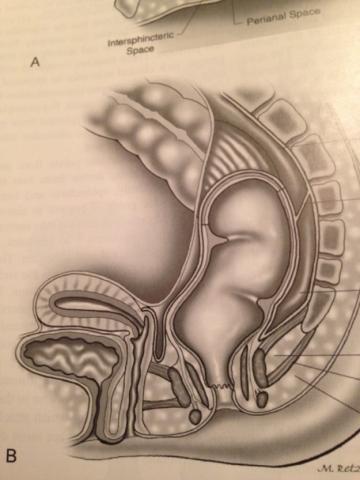

While the external anal sphincter squeezes, the inner muscle that encircles the anus, called the internal anal sphincter, relaxes to allow stool to enter the anal canal. When stool enters the anal canal, sensory nerves in the anus identify the difference between gas and stool and determine the consistency of the stool (liquid versus solid). Signals are sent to the brain indicating the need to have a bowel movement. If the person has a socially appropriate time and place to have a bowel movement, the anal sphincter muscles, as well as the muscles of the pelvic floor, relax and the abdominal muscles tighten to expel the stool (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Normal anatomy of anus and rectum, Male

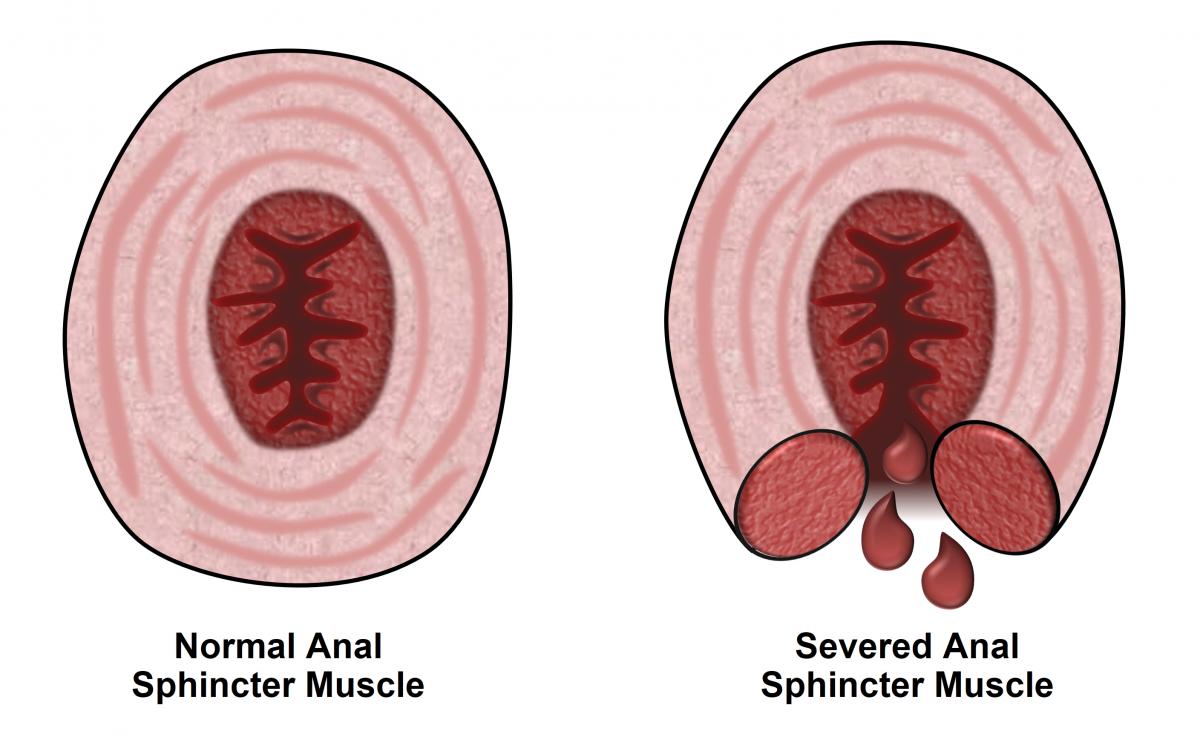

Fecal incontinence, or loss of control, can occur if the person has loose stools, or if they have diseases or injuries to the rectum, the anus, or the nerves that control the anal muscles. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Normal anus and sphincter injury

Fecal incontinence is a major burden to both patients and society. Patients are often significantly embarrassed as a result of accidents or soiling of clothing. Unfortunately, many of these patients suffer in silence because they are afraid even to discuss it with their own family or physician. Incontinence can lead to a patient changing their lifestyle in avoidance of certain social activities, changes in employment, and can strain personal relationships. All of these things can negatively impact a patient’s quality of life. Medical costs, supply costs, and days lost from work all place a significant burden on society as well.

HOW COMMON IS FECAL INCONTINENCE?

It is difficult to identify the exact number of people who have fecal incontinence in the general population. One of the difficulties in measuring how many people have fecal incontinence is that patients questioned about incontinence often under-report their symptoms. Studies in the literature show rates of fecal incontinence between vary from 1.5-18% of the general.

Fecal incontinence is approximately twice as common among women as it is among men. Thirty percent of those who reported incontinence were older than age 65. It is a much more common condition than many people believe. It is important that patients not feel alone or have a fear bringing fecal incontinence issues to the attention of their health care providers. Treatment for fecal incontinence can significantly improve a patient’s quality of life.

WHO IS AT RISK FOR FECAL INCONTINENCE?

A risk factor is something that increases a person’s chance of getting a disease or problem. There are many risk factors for fecal incontinence, including:

-

Female gender – fecal incontinence is approximately twice as common among women as men. Injury to the anal sphincter complex during childbirth is common, and this may include a tear in the sphincter muscles and/or injury to the pudendal nerves, which are the nerves that control the anal muscles.

-

Increasing age – fecal incontinence is more common among older adults than in the population in general. The overall function of the anus may worsen as people age. Additionally, neurologic diseases that can affect anal function are more common in older adults.

-

Poor general health – fecal incontinence is very common among nursing home and hospitalized patients and may be due, in part, to a decreased mobility, making it difficult for the patient to get to the bathroom.

-

Prior pregnancy – changes in continence can occur after childbirth, especially after prolonged labor, an episiotomy (surgical incision), or the use of instrumentation such as vacuum assistance and forceps. Undiagnosed injury to the anal sphincter can occur in up to 35% of women who undergo a vaginal delivery. Younger women may be able to compensate by using other pelvic floor muscles, but they may develop fecal incontinence as they become older.

-

Prior anorectal surgery – people who have had surgery for an anal fissure (small tear in the anus), an anal fistula (abnormal passageway between the bowel and nearby organs or between the bowel and skin), or hemorrhoids are at risk for fecal incontinence.

-

Prior rectal resection — patients who have had part or their entire rectum removed are at risk for fecal incontinence, because the reservoir function of the original rectum is difficult to reproduce.

-

Pelvic radiation – pelvic radiation can injure the nerves that control the anus and/or decrease the elasticity in the rectum, which increases the risk for fecal incontinence.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF FECAL INCONTINENCE?

The symptoms of fecal incontinence can range from minor changes in the ability to control gas to complete loss of control of solid stool without warning, and varying degrees in-between. Some patients may experience symptoms only intermittently on a weekly or monthly basis, where others may experience incontinence daily. Some patients’ symptoms may be exacerbated by a change in the consistency of stool, and it is common for patients to report normal control when their stools are solid, but report a loss of control with liquid stool.

Patients may also have altered awareness of their need to have a bowel movement. They may report having no sense of the need to have a bowel movement, and may have spontaneous loss of solid or liquid stool. Patients may report a minor loss of liquid stool which only stains undergarments — sometimes referred to as “seepage” or “staining”.

Patients may also report new symptoms of urgency or “near accidents”. This occurs when the patient can sense the need to have a bowel movement but cannot “hold it” for a long time without an accident. Patients may say they need to stay close to a bathroom at all times and may avoid situations where they do not have easy access to a bathroom.

HOW IS FECAL INCONTINENCE DIAGNOSED?

Diagnosing fecal incontinence involves taking an adequate medical history from patients and carefully listening to their complaints, as the many causes and symptoms of fecal incontinence are varied. Providers will often ask questions to clarify:

-

the severity of the symptoms, which includes the frequency of incontinence to gas, liquid, or solid stool,

-

the patient’s ability to sense the need to have a bowel movement,

-

the impact of the symptoms on the patient’s life, including the need to wear a pad.

Providers may use a scoring system to quantify the severity of the symptoms.

The history will also include a thorough medical and surgical history. These questions may include the number and nature of any prior anal or rectal operations, any history of diarrhea, any history of colitis (inflammation of the colon), other pelvic floor complaints such as urinary incontinence or rectal prolapse (when the rectum turns inside out and hangs outside the body), a history of neurologic diseases, medications, and a complete obstetric history.

Once the history of fecal incontinence is established, a complete physical examination may help confirm the causes of the incontinence and may assist the treatment planning. Examination may include a visual exam of the anus and surrounding skin, a digital rectal examination of the anus, and anoscopy, which is visualization of the anal canal with a small scope.

Further testing may be required to confirm the exact cause of the patient’s incontinence. One of the most common examinations performed is an anal ultrasound. During this test, a small ultrasound probe is inserted into the anal canal, and the ultrasound machine is able to generate pictures which can demonstrate abnormalities of the anal muscles. Ultrasound examination is particularly important for planning surgical repair of the muscles.

Another common test is called an anorectal manometry. In this test, a small pressure sensor is inserted into the anus to measure pressures within the anus and rectum. The patient may be asked to squeeze as if holding in a bowel movement or to note sensation within the rectum as small balloon at the tip of the pressure sensor is distended. This provides information on how well your muscles can squeeze, as well as how well your rectum is functioning as a reservoir for stool.

Other tests to evaluate fecal incontinence include colonoscopy, electromyography with testing of the pudendal nerves, and defecography. Colonoscopy is a visualization of the inside of the colon with a flexible scope and can identify any underlying diseases such as colitis or to rule out any co-existing problems such as polyps or cancer. Electromyography (EMG) and testing of the pudendal nerves is done to assess the nerves that control the anus and can help evaluate neurologic causes of the incontinence. Defecography is a radiologic examination that uses x-rays or an MRI to examine the patient during the act of having a bowel movement. This can be done to assess for proper coordination of the pelvic floor muscles as well as other anatomic causes of the incontinence.

HOW IS FECAL INCONTINENCE TREATED?

There are a variety of treatments for fecal incontinence that include non-invasive treatments, medications, and surgical treatments. It is important to note that not all treatments will be appropriate for all patients. Additionally, patients are always at liberty to delay treatment or to do nothing once the underlying cause of incontinence is discovered and once treatment options are discussed. For example, incontinence due to a long-standing injury to the anal muscles is not likely to get better without treatment, but there is also little risk in delaying or avoiding treatment. On the other hand, delay in a treatment of an underlying colitis may have serious medical consequences. The specific risks and benefits of each treatment option should be discussed with a provider.

Regardless of what type of therapy is offered, patients must have realistic expectations regarding the outcomes of treatment. A realistic goal may be to restore the patient to a more livable situation, where they can resume many of the activities they have previously enjoyed, but not necessarily restore them to perfect continence.

NON-SURGICAL THERAPY

There are several therapies for fecal incontinence that do not include an operation. Non-surgical options include dietary changes, medications to bulk the stools, constipating medications, and biofeedback. For milder forms of incontinence, a trial of these non-operative therapies is often the best option to try first. Dietary changes include avoiding foods that cause diarrhea and increasing intake of foods high in fiber including whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and nuts. Fiber acts by holding on to water within the stool and increasing the bulk of the stool, which may improve rectal sensation for the need to have a bowel movement or may decrease episodes of minor seepage. It is often difficult to include a large amount of fiber in one’s diet, even when “eating healthy,” so fiber supplements may be prescribed when patients are not able to consume an adequate amount of fiber in their diet.

Constipating medications such as loperamide (Imodium™) or dephenoxylate with atropine (Lomotil™) may be used to treat patients with diarrhea. It is generally easier for the anus to control solid stool than liquid stool, so changing the consistency of the stool from liquid to solid may provide some decrease in symptoms.

Biofeedback is a form of therapy where visual, auditory, and other forms of sensory information are used to improve a patient’s ability to detect the need to have a bowel movement, and to reinforce the appropriate sphincter muscle response. These sessions are done with specially trained therapists. Patients can be taught appropriate exercises to strengthen the anal sphincters and the muscles of the pelvic floor.

SURGICAL THERAPY

Surgical therapies for fecal incontinence include injection of biomaterials into the anal canal, radiofrequency treatment of the anal canal, repair of anal muscle injuries, sacral nerve stimulation, artificial bowel sphincter, muscle transposition to reinforce the anal sphincter, and creation of a stoma.

Injection of biomaterials into the anal canal can help bulk up the anal canal and reinforce squeeze mechanism of the anus. The most commonly used materials are silicone or carbon coated microbeads or dextranomer (Solesta™). This therapy is an attractive option since it is minimally invasive without the need for major surgery. The procedure is often performed in an office setting, and is done with local anesthesia or occasionally with some sedation.

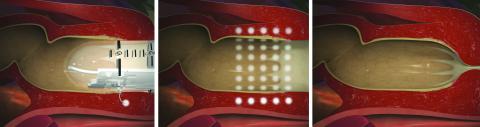

Previously, delivery of radiofrequency energy to the anal canal has been used for treatment of fecal incontinence. This technique has been rarely employed over the past several years. The exact mechanism of how this technique works is not well understood. The procedure is generally done in an operating room with sedation anesthesia and local anesthesia. A probe is used to deliver the energy to the anal canal, which may cause some scarring or tightening of the anal muscles. (see Figure 4).

Figure 4 The Secca procedures for fecal incontinence

Figure 4 The Secca procedures for fecal incontinence

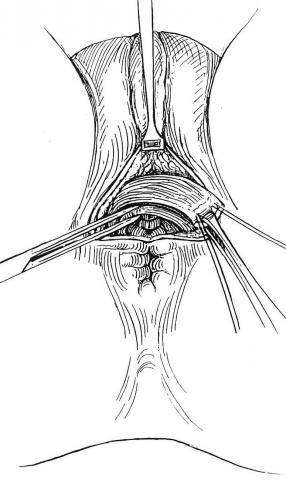

Direct repair of injured anal sphincter muscles (sphincteroplasty) is a well-established therapy for patients with incontinence due to a sphincter injury. The most common cause of sphincter injury occurs during childbirth, and direct repair of the injured muscles can improve the effective function of the anal muscles. This type of repair is done in the operating room with the patient under general anesthesia, and patients are usually kept in the hospital overnight. This technique to repair the anal sphincters has been around for several years and has been well studied, and the studies show that initial results are often good, but patients may have recurrence of their incontinence over extended periods of time. (see Figure 5.)

Figure 5. Overlapping sphincteroplasty

Figure 5. Overlapping sphincteroplasty

Sacral nerve stimulation is a procedure where an electrical lead is placed within the sacrum (“tailbone”) to stimulate the nerves that control the anus and surrounding structures. The stimulation is done by a nerve stimulator similar to a heart pacemaker. This procedure is unique in that it is done in a staged manner. First, the leads are placed within the sacrum and the wire is placed to an external stimulator the patient wears for two weeks. Patients keep a diary of bowel habits before and after lead placement, and patients who have had greater than 50% reduction in incontinent episodes during the two weeks will have a permanent nerve stimulator placed. The permanent nerve stimulator sits below the skin within the buttocks. The exact mechanism of how sacral nerve stimulation works is not well understood. Results of this procedure from studies in North America and Europe demonstrate that as many as 80% of patients will have a significant decrease in incontinence episodes with this therapy. (see Figure 6)

Figure 6. Diagram of Sacral Nerve Stimulation

Figure 6. Diagram of Sacral Nerve Stimulation

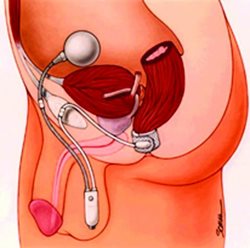

The artificial bowel sphincter is a procedure where a plastic cuff with a balloon is placed around the anus. This procedure is rarely employed and is performed only at isolated centers around the country. The balloon is filled with fluid and is connected to a reservoir that can inflate or deflate the plastic cuff. When patients need to have a bowel movement, the reservoir can be filled by actively squeezing a pump that sits underneath the skin of the labia or the scrotum, which deflates the cuff by moving the fluid from the cuff into the reservoir and allow stool to pass through the anus. The artificial bowel sphincter is placed in the operating room under general anesthesia. Care must be taken to avoid infection since this is an artificial device. (see Figure 7.)

Figure 7. Diagram of artificial bowel sphincter placement in men and women

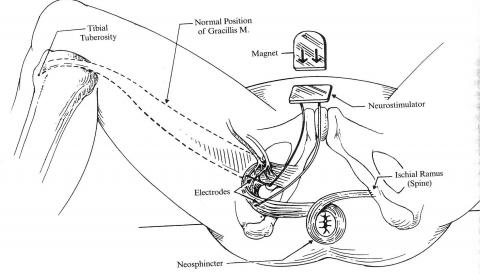

A gracilis interposition is a technique where a muscle from the leg, the gracilis muscle, is dissected from the leg and pulled up to be placed under the skin around the anal canal. This technique can assist the squeeze mechanism of the anal muscles and improve incontinence. The main risk of this procedure is infection, bleeding, and need for revisions. This technique is not commonly used but remains a viable alternative in selected patients. (see Figure 8.)

Figure 8. Gracillis Interposition

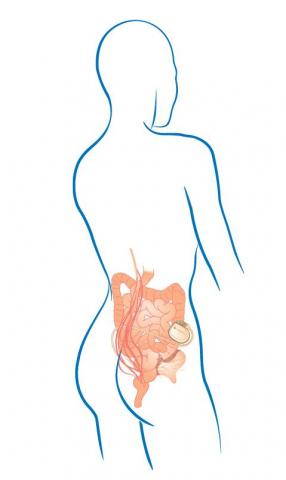

Finally, creation of a colostomy may be the most appropriate treatment for some patients who have not had success with other therapies or who are severely debilitated. Creation of a colostomy involves bringing the bowel through the abdominal wall so that it empties its contents into a bag that sits on the abdominal wall. While most patients are initially hesitant to undergo this procedure, the majority are happy afterward because it restores them to a manageable, predictable state with regard to their bowel function. Colostomies are performed in the operating room under general anesthesia. As with any abdominal operation, the risks to these procedures include infection and bleeding. (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Normal Colostomy

Figure 9. Normal Colostomy

CONCLUSION

Fecal incontinence can be a debilitating condition, and it has a wide variety of causes and symptoms. The many techniques to treat fecal incontinence include both non-surgical and surgical therapies. A thorough discussion with a provider is needed to evaluate the severity, causes, and possible therapies for each patient.

QUESTIONS FOR YOUR SURGEON

-

What tests do you plan to do to evaluate incontinence?

-

How severe is a patient’s fecal incontinence?

-

What are some realistic goals to aim for regarding incontinence?

-

What are the non-surgical options for treatment of incontinence?

-

How successful are non-surgical treatments for incontinence, and what are the risks?

-

What are the surgical options for treatment of incontinence?

-

How successful are the various surgical treatments, and what are the risks?

-

If a particular treatment does not work, are there backup options?

-

What to expect after surgery?

-

How will you treat pain after surgery?

-

Are there risks to not treating incontinence?

WHAT IS A COLON AND RECTAL SURGEON?

Colon and rectal surgeons are experts in the surgical and non-surgical treatment of diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. They have completed advanced surgical training in the treatment of these diseases as well as full general surgical training. Board-certified colon and rectal surgeons complete residencies in general surgery and colon and rectal surgery, and pass intensive examinations conducted by the American Board of Surgery and the American Board of Colon and Rectal Surgery. They are well-versed in the treatment of both benign and malignant diseases of the colon, rectum and anus and are able to perform routine screening examinations and surgically treat conditions if indicated to do so.

DISCLAIMER

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to ensuring high-quality patient care by advancing the science, prevention and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. These brochures are inclusive but not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on diseases and processes, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. They are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed. It should be recognized that these brochures should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of methods of care reasonably directed to obtain the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

SOURCES

Beck, et al. The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery. Second Edition. Springer Inc. New York. 2011

Tjandra, J. L., et al. Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Oct;50(10):1497-507

Kaiser, A. M. Fecal Incontinence. ASCRS Core Subjects. 2009 ASCRS Annual Meeting

SELECTED READINGS

National Institutes of Health http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/fecalincontinence/index.aspx

Mayo Clinic Website http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/fecal-incontinence/DS00477