OVERVIEW

The purpose of this education piece is to provide information on the background, causes, and treatments of diverticular disease and its complications. This information is intended for a general audience. Diverticular disease most commonly affects adults and may be managed medically or surgically, depending on patient circumstances. Successful treatment of diverticular disease not only relieves symptoms, but often improves the quality of life for these patients.

WHAT IS DIVERTICULAR DISEASE?

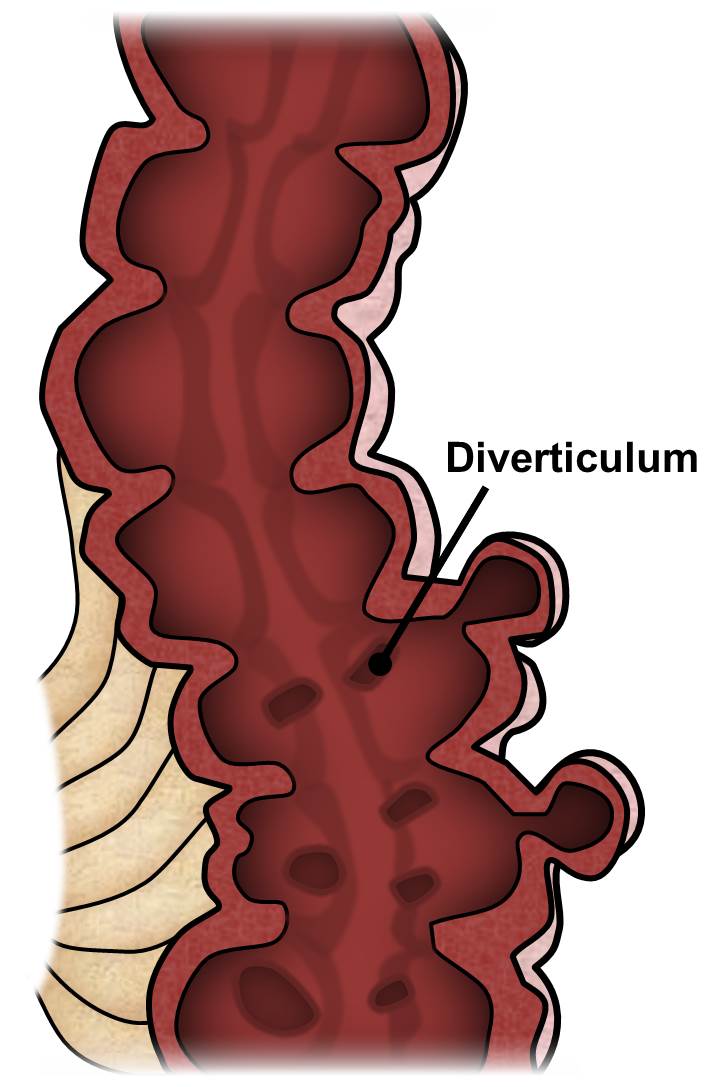

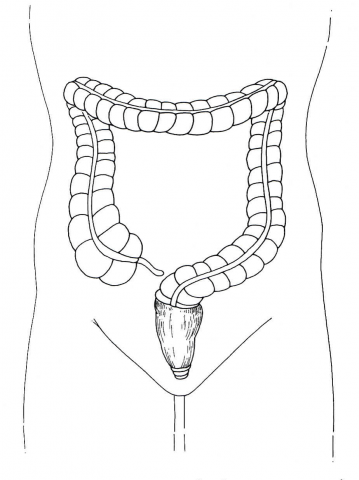

Diverticular disease is the general name given to the disease that creates small sacs or pouches from the wall of the colon and the complications that can arise from the presence of those sacs. There are many terms related to diverticular disease that can be confusing and deserve to be defined. The individual sacs or pouches are called a diverticulum. Multiple sacs or pouches (the plural form of the word diverticulum) are called diverticula (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diverticulosis

The term diverticulosis refers to simply having diverticula within the colon but without complications or problems from those sacs. The presence of diverticulosis can lead to several different complications such as diverticulitis, perforation, stricture, fistula, and bleeding. All of these complications will be discussed in detail below.

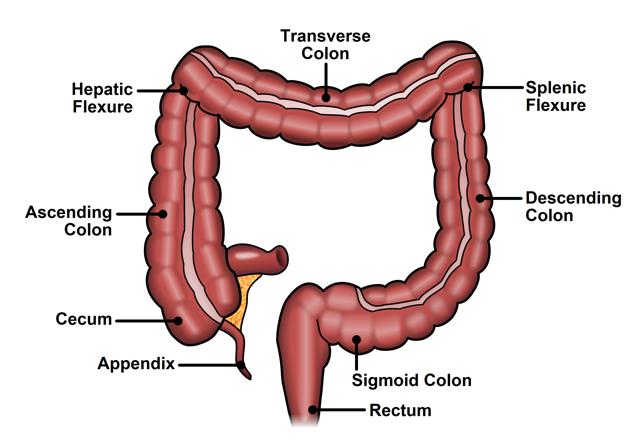

The colon, rectum, and anus are parts of the digestive system. They form a long, muscular tube called the large intestine (together called the large bowel). The colon is the first 4 to 5 feet of the large intestine; the rectum is the next six inches, and the anus (opening) makes up the final 1-2 inches. Different portions of the colon have specific names. These portions are named the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. The ascending and descending are relatively fixed in place while the transverse colon and sigmoid colon are relatively mobile (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Normal anatomy of the colon and rectum.

Partly digested food enters the colon from the small intestine. The colon removes water and nutrients from the food and turns the rest into solid waste (stool). Coordinated series of contractions of the colon act to pass the stool forward and empty into the rectum. As stool enters the rectum, the rectum relaxes and acts as a reservoir to hold the stool. The primary function of the anus is to hold stool within the rectum until a time when it is appropriate to pass stool (defecate or have a “bowel movement”). At the appropriate time, the anus relaxes to eliminate the stool.

Diverticula can form throughout the colon but, in the United States and other Western countries, the sigmoid colon is the most common site for diverticula to form. Diverticula of the cecum and ascending colon are seen occasionally in the United States but are much more common in Asia.

The exact cause of diverticulosis is not known. The most commonly accepted theory is that low amounts of fiber in a person’s diet causes the stool to become dry, forcing the colon to create higher pressures to move the stool through the colon. These high pressures cause the weakest points of the colon wall to bulge out, especially at points where blood vessels penetrate the wall of the colon. Along with the formation of diverticula, higher colonic pressures may cause the muscles of the colon wall to become enlarged, or hypertrophied.

Diverticulosis is very common, and the proportion of the population with diverticulosis increases with age. It is uncommon for people under the age of 30 to have diverticulosis, but approximately 30-40% of people aged 60 years old have diverticulosis and up to 50-80% of people aged 80 years old have diverticulosis. Most people with diverticulosis will not have symptoms from it. In fact, only 10-20% of people with diverticulosis will develop symptoms, and of the people that develop symptoms, only 10-20% of those people will need hospitalization and only about 1% will require surgery.

The most common complication of diverticulosis is diverticulitis. Diverticulitis is an inflammatory condition of the colon that is thought to be caused by perforation of one of the individual sacs. It is estimated that 10-20% of people with diverticulosis will develop diverticulitis. The most common symptoms of simple diverticulitis are abdominal or pelvic pain, abdominal tenderness, and fevers. Complicated diverticulitis occurs when secondary complications results after an attack of diverticulitis, and these complications include abscess formation and perforation of the colon with peritonitis. An abscess is a pocket of pus that the body has walled off, and peritonitis is infection that spreads freely within the abdomen. Peritonitis often causes patients to become quite sick and may be life threatening.

Complicated diverticulitis is often graded on a scale called the Hinchey classification. Hinchey 1 refers to the presence of an abscess near the inflamed segment of colon. Hinchey 2 is the presence of an abscess within the pelvis that is separate from the inflamed segment of colon. Hinchey 3 refers to a perforation of the colon that results in spread of infection within the abdomen (peritonitis). Hinchey 4 refers to perforation of the colon resulting in spillage of stool within the abdomen.

Once a person has an attack of diverticulitis, he or she is at risk for further episodes and for the development of complications. It is difficult to define the exact risk of a recurrent attack of diverticulitis in a person who has had a previous attack, and there are many factors that may influence this risk, including the age of the patient and the severity of the initial attack. The most feared complication of diverticulitis is perforation and peritonitis, which often requires emergency surgery and the creation of a colostomy. Several studies have demonstrated that the vast majority of patients in whom this happens have never had prior symptoms from their diverticula.

Other complications of diverticulosis include bleeding, formation of a narrowing in the colon that does not easily let stool pass (called a stricture, see Figure 4), or formation of a tract to another organ or the skin (called a fistula). When a fistula forms, it most commonly connects the colon to the bladder. It may also connect the colon to the skin, uterus, vagina, or another portion of the bowel.

Chronic diverticulitis is the condition where patients may have repeated attacks of diverticulitis or may have a prolonged course of a single attack of diverticulitis. Chronic diverticulitis also refers to the complications that arise from repeated attacks of diverticulitis such as stricture and fistula.

Finally, diverticular sacs can bleed. Bleeding may be minor in the form of a small amount of red blood that is mixed in with the stool during an attack of diverticulitis, or the bleeding may be severe, involving the passage of dark clots of blood that may or may not happen during an attack of diverticulitis. The treatment of diverticular bleeding differs significantly from other forms of diverticular disease, Briefly, most cases of bleeding will stop with supportive care in the hospital or with minimally invasive techniques such as angiography or colonoscopy. Angiography is a technique where a wire is advanced through the blood vessels in order to identify the source of bleeding, and angiography may also permit the injection of substances under radiologic guidance in order to stop the bleeding. If bleeding remains uncontrolled or ongoing, surgery to remove part or the entire colon may be necessary.

WHO IS AT RISK FOR DIVERTICULAR DISEASE?

A risk factor is something that increases a person’s chance of getting a disease or problem. There are many risk factors for diverticular disease including:

-

Low fiber diet. Diets that are low in fiber, fruits, and vegetables and are high in red meat are risk factors for developing diverticular disease. A diet that lacks fiber may increase the risk by three times, so adding fiber to your diet may help protect the colon from diverticular disease. In the past, patients with diverticulosis were told to avoid nuts, seeds, and popcorn, as it was felt that this may increase the risk of diverticulitis, but more recent studies that have found this recommendation not to be true.

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Use of NSAIDs such as ibuprofen for conditions such as arthritis has been associated with complications of diverticulosis.

-

Immune status. Patients whose immune systems are suppressed from medications (steroids or anti-rejection medications for a transplanted organ) are at risk for more severe complications such as colonic perforation.

-

Alcohol. Excessive consumption of alcohol may raise the risk of diverticulitis by 2-3 times as compared to the general population.

-

Age and gender. It is unclear the extent to which age and gender are a risk factor for complications from diverticulosis. Women tend to have complications from diverticulosis later in life than men. It was once thought that patients who have an attack of diverticulitis before age 50 would have a more virulent form of the disease, but this does not seem to be the case.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF DIVERTICULAR DISEASE AND HOW IS IT DIAGNOSED?

As mentioned, most patients with diverticulosis have no symptoms. The most common symptoms of diverticulitis are abdominal pain and fever. The abdominal pain of diverticulitis is usually lower and/or left-sided abdominal pain. The pain is usually sharp and constant, and the pain may seem to travel, or radiate, to the leg, groin, back, and side. A change in bowel habits such as diarrhea or constipation may also be seen. Patients may also have urinary symptoms such as increased need to urinate and urinary urgency.

Patients with complications of their diverticulitis may have more chronic or long-term, symptoms. Thin stools or constipation may indicate the formation of a stricture. Dark, cloudy urine or passing air with the urine may indicate the formation of a fistula to the bladder.

Diverticular disease and its complications are usually diagnosed through the patient’s history and physical examination, often with the aid of diagnostic tests. Symptoms such as abdominal pain and tenderness are not specific to diverticulitis, and it is important to distinguish diverticulitis from diseases that can involve other organs in the abdomen such as the appendix, gallbladder, stomach, small bowel, ovaries, uterus, prostate and bladder. A careful history and physical can help narrow down the diagnosis or eliminate other diagnoses.

The most common tests to help make the diagnosis of diverticulitis and its complications are blood tests, urine tests, and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. A CT scan is considered the “gold standard” for diagnosing diverticulitis. It can show what part of the colon is involved, and if there is any sign of abscess, stricture, or fistula. Blood tests are often performed, and an elevated white blood cell count may indicate the presence of infection. An analysis and culture of the urine may detect a urinary tract infection, raising suspicion of a fistula from the colon to the bladder, as the urine would be contaminated with stool from the colon.

HOW CAN DIVERTICULAR DISEASE BE TREATED?

Diverticular disease can develop in many forms and patients may present with various degrees of severity. As might be expected, there is no one best treatment for all forms of diverticular disease. The following discussion will attempt to describe various common treatments for different ways people can present with diverticular disease.

Most people with diverticulosis will never develop problems from it. Patients who are diagnosed with diverticulosis on a routine colonoscopy or by other testing, and otherwise do not have symptoms of diverticulitis, are advised to consider increasing the fiber in their diet. Although the ideal amount of fiber to decrease diverticulitis attacks or other problems from diverticulosis is not known, it is generally recommended that people with diverticulosis consume about 20-30 grams of fiber per day.

When discussing the treatment options for diverticulitis, it is convenient to separate treatment options into two categories: treatment for acute diverticulitis and treatment for chronic diverticulitis.

Treatment for acute diverticulitis involves the treatment of a new and ongoing attack of diverticulitis. Most patients with an acute attack of diverticulitis will find relief with antibiotics and temporary changes in diet. Most of these patients will not require hospitalization. Patients without significant fever or change in heart rate or blood pressure who can tolerate taking in oral liquids can be treated with oral antibiotics and restriction of the diet to a low fiber or liquid only diet until the attack resolves.

Patients who have signs of a more serious attack, such as high white blood cell count, high fever, changes in heart rate or blood pressure, or patients who do not get better with oral antibiotics, will have to be admitted to the hospital for hydration and intravenous (IV) antibiotics. A colonoscopy is often recommended several weeks after recovery from an initial attack of diverticulitis to make sure there is not another cause for recent illness (cancer or other inflammatory condition of the colon). (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Colonoscopy

Figure 3. Colonoscopy

Citation: Terese Winslow, National Cancer Institute

Patients who have a severe attack of diverticulitis are at risk for forming an abscess. An abscess is pocket of pus that results from rupture of an inflamed diverticulum, and abscesses can be detected on CT scans. Small abscesses may be treated with antibiotics alone, but larger abscesses may require a procedure called “percutaneous drainage,” which is a procedure that uses radiologic imaging to place a drain through the skin into the abscess.

Surgery for acute diverticulitis is limited to a few circumstances. These include:

-

An attack of diverticulitis that causes the colon to perforate, resulting in pus or stool leaking into the abdominal cavity and causing peritonitis. Patients with colonic perforation are usually quite ill, and present with severe abdominal pain and changes in heart rate and blood pressure. These patients often require emergency surgery.

-

An abscess that cannot be safely drained with percutaneous drainage, or if the percutaneous drainage was ineffective.

-

The patient fails to improve with appropriate medical therapy, including IV antibiotics and hospitalization.

-

Aggressive treatment, including surgery, is often required for patients who are immunocompromised (patients who have received an organ transplant or who are receiving chemotherapy).

There are several surgical options for the treatment of acute diverticulitis. Laparoscopic (minimally invasive) or traditional open surgical techniques may be used for all these options. Laparoscopic surgery refers to a technique where the surgeon makes several small incisions (usually about ½” in size), instead of a single large incision. For most colon and rectal operations, 3-5 incisions are needed. Small tubes, called “trocars,” are placed through these incisions and into the abdomen, and carbon dioxide gas is used to inflate the abdomen. The surgeon uses a camera attached to a thin metal telescope (called a laparoscope) to view inside the abdomen. Special instruments have been developed for the surgeon to pass through the trocars to take the place of the surgeon’s hands and traditional surgical instruments.

Many factors go into the choice of a particular operation and operative technique. These include the overall health of the patient, their current clinical status, the patient’s underlying continence or control of gas and stool, and the surgeon’s preference or experience with these techniques. The overall goal is to control the infection and return the patient to good health while minimizing the risks of serious complications.

The options for surgical treatment include:

-

removal of the involved part of the colon, with or without creation of a colostomy,

-

a washout of the abdominal cavity and leaving the colon in place, or

-

creating an ostomy (a surgically created opening between an internal organ and the body surface) to divert the fecal stream without removal of the colon.

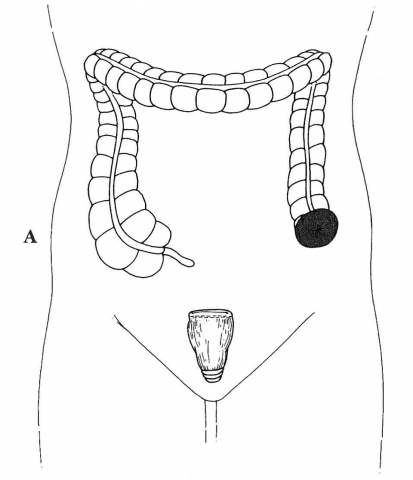

Removal of the affected portion of the colon, usually the sigmoid colon, is the most common procedure for surgical treatment of acute diverticulitis. Once that portion of the colon is removed, the surgeon must decide on whether to reconnect the colon to the rectum or create a colostomy. A colostomy is a procedure where the end of the bowel is brought out through the abdominal wall and the stool empties into a bag that attaches to the skin (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Sigmoid resection and end colostomy

Citation: Gordon, P. Nivatvongs, S. Eds. Principles and Practice of Surgery of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus. Quality Medical Publishing, St. Louis, MO. 1992. pg 766.

Reconnecting the colon and avoiding an ostomy is a great advantage to the patient. Reversal of a colostomy at a later date can be a challenging procedure, and is associated with significant risks. However, there is also a risk that reconnecting the colon may not heal properly, resulting in a leak from the colon and ongoing infection. The risk of leak is thought to be higher, 6-19% vs. 5%, when the patient is acutely sick from diverticulitis.

In order to minimize the risks of colon leak, your surgeon may choose to protect the reconnected bowel by bringing out a piece of small intestine. This procedure, called a protective loop ileostomy, allows the stool to pass out of the body and avoid the reconnected bowel as it heals. After 2-3 months, the healing process of the bowel should be complete and the ileostomy may be reconnected, removing the ostomy and allowing stool to pass normally below. Your surgeon will evaluate the risks involved with any of these scenarios, and then carefully consider the option that is best for any particular patient.

An alternative strategy emerging only in recent years, for the treatment of acute complicated diverticulitis, is to perform a laparoscopic washout of the abdomen. This technique involves using laparoscopic techniques to inspect the abdomen, drain any pus, and wash out the abdominal cavity. The goal is to remove the infected fluid, place a drain to control any additional effluent, allow the colon to heal, and avoid surgically removing the involved portion of the colon, when possible, in the acute setting or, in some cases, altogether. This technique has most often been used for patients with an abscess or perforation of the colon and spread of infection, but without spread of stool into the abdomen.

The main criticism of this technique is that the inflamed section of colon remains in place, putting the patient at risk for ongoing or recurrent infection. This is a relatively new technique and compared to traditional management strategies, the results as are not well defined. Studies are underway to see if this technique has an appropriate role in managing patients with diverticulitis.

Treatment of chronic diverticulitis involves treatment of recurrent disease, or the complications that may result from an acute attack. In general, treatment for chronic diverticulitis involves surgery to remove the involved portions of the colon, usually the sigmoid colon, and then reconnecting the colon (see Figure 8). This operation may be done with either laparoscopic or traditional open techniques. The main benefits of laparoscopic surgery are a smaller incision size and a quicker recovery (see Figure 5).

It is not necessary to remove all of the parts of the colon that have diverticula. It is only necessary to remove the portion of the colon that is diseased, and to ensure that the reconnection of the colon is done between soft, non-diseased portion of colon and the rectum.

Figure 5. Sigmoid resection and anastomosis

Figure 5. Sigmoid resection and anastomosis

Citation: Gordon, P. Nivatvongs, S. Eds. Principles and Practice of Surgery of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus. Quality Medical Publishing, St. Louis, MO. 1992. pg 770.

There are many risks associated with colon surgery. As discussed above, there is a risk that the reconnection will not heal properly and the colon can leak stool. Because an operation for chronic diverticulitis is usually done electively, the risk of a colon leak is lower than if the operation is performed in an emergency.

The most common risk associated with colon surgery is infection. Surgery may result in a wound infection, which may be limited to the skin and underlying fat, or may result in an infection that spreads within the abdomen. Wound infections are treated by opening the wound and dressing changes, but deeper infections are treated with antibiotics and either percutaneous drainage or open operation.

The sigmoid colon lies directly over the left ureter, which is the tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder. During surgery, there is a risk that the left ureter may be injured while removing the sigmoid colon, especially if there have been many attacks of diverticulitis. In order to reduce this risk your surgeon may ask a urologist to place a stent, or tube temporarily, in one or both of the ureters as part of your operation in order to help identify, and avoid injury to, the ureters during surgery.

Patients who undergo surgery are also at risk of a urinary tract infection, because they often have a catheter to drain the bladder during and after surgery. Other risks of surgery include, but are not limited to, post-operative pneumonia, heart attack, stroke, blood clots in the legs and some times in the lungs, organ failure, and even death.

Since there are significant risks associated with surgery, the benefits obtained from surgery must outweigh the risks. The main benefits of surgery for chronic diverticulitis are to prevent recurrent attacks, or cure the complications of diverticulitis such as stricture or fistula.

A patient who has had an attack of diverticulitis is at risk for a repeat attack. The risk of a repeat attack after an initial attack of uncomplicated diverticulitis is low, with rates ranging widely from 1.4% to 18%. The risk of a repeat attack increases with each subsequent attack. It was previously thought that repeated attacks placed a patient at risk for emergency surgery and need for a colostomy, therefore a pre-emptive resection of the sigmoid colon, after the patient had recovered and the patient was doing well, was often recommended to prevent the need for emergency surgery.

It has since been found that the risk of needing emergency surgery after an attack of uncomplicated diverticulitis is low. The severity of prior attacks also affects the risk of future attacks. For example, patients who had an acute attack with an abscess that was treated with a percutaneous drain are at higher risk for recurrence. However, despite this higher risk, there is evidence that some patients who have been successfully treated for an abscess will do well without surgery. Therefore, the decision to proceed with a colon resection to prevent future attacks should be based on the number and severity of prior attacks, the presence of ongoing symptoms from prior attacks, and the age and general medical condition of the patient.

The indications for surgery are more definite when a stricture or fistula forms as a result of diverticular disease. A stricture is a narrowing of the colon that may partially block passage of stool. In rare cases, the stricture may become so severe that it causes complete obstruction (blockage) of the bowel. A fistula is an abnormal connection from the colon to another organ. Fistulas may form to the bladder, uterus, vagina, skin, or other portions of the bowel. Surgery for both fistula and stricture includes removal of the sigmoid colon with reconnection of the colon or creation of an ostomy, as described above. Surgery for a fistula may also include a repair or resection of the organ which is involved in the fistula. These procedures may involve removal of an additional segment of bowel, repair of the bladder, repair of the vagina, or repair of the uterus or hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) in severe cases.

In summary, diverticular disease is a common condition, especially among older adults. It may present with a wide range of symptoms and severity, ranging from asymptomatic disease to life threatening abdominal infections. There are several treatment strategies with the majority of therapies consisting of conservative measures such as a change in diet or antibiotics. Surgery may play a curative role, especially in more advanced cases.

QUESTIONS FOR YOUR SURGEON

-

What tests do you plan to do to evaluate my diverticulitis?

-

Compared to other patients, how severe is my diverticulitis?

-

What are some realistic goals to aim for regarding my diverticulitis?

-

What are the non-surgical options for treatment of my diverticulitis?

-

How successful are non-surgical treatments for diverticulitis and what are the risks?

-

What are the surgical options for treatment of my diverticulitis?

-

How successful are the various surgical treatments and what are the risks?

-

If a particular treatment does not work, are there backup options?

-

What can I expect after surgery?

-

How will you treat my pain after surgery?

-

Are there risks to not treating my diverticulitis?

WHAT IS A COLON AND RECTAL SURGEON?

Colon and Rectal Surgeons are experts in the surgical and non-surgical treatment of conditions of the colon, rectum, and anus. Board-certified colon and rectal surgeons have completed residencies in both General Surgery and Colon and Rectal Surgery, and have passed intensive examinations conducted by the American Board of Surgery and the American Board of Colon and Rectal Surgery. This advanced surgical training makes them well-versed in the treatment of both benign and malignant diseases of the colon, rectum, and anus, and they are able to perform routine screening examinations and surgically treat conditions when needed.

DISCLAIMER

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to ensuring high-quality patient care by advancing the science, prevention and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. These brochures are inclusive but not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on diseases and processes, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. They are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed. These brochures should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of methods of care reasonably directed to obtain the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

SOURCES

Thorson, A. G. and Beaty, J. S. Chapter 22, “Diverticular Disease”. Chapter in Beck, D.E., Roberts, P. L., Saclarides, T. J., Senagore, A. J., Stamos, M. J., Wexner, S. D., Eds. ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery, 2nd edition. Springer, New York, NY; 2011.

Rafferty, J., et al. Practice Parameters for Sigmoid Diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006 Jul;49(7):939-44.

McNevin, M. S. Diverticulitis. ASCRS Core Subjects. 2009 ASCRS National Meeting.

SELECTED READINGS

US National Library of Medicine http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001303/

Mayoclinic.com http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/diverticulitis/DS00070

National Institutes of Health http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/diverticulosis/