WHAT IS RECTAL PROLAPSE?

Rectal prolapse is a condition in which the rectum (the last part of the large intestine before it exits the anus) loses its normal attachments inside the body, allowing it to telescope out through the anus, thereby turning it “inside out.” While this may be uncomfortable, it rarely results in an emergent medical problem. However, it can be quite embarrassing and often has a significant negative impact on patients’ quality of life.

Overall, rectal prolapse affects relatively few people (about 0.5% of the general population). This condition affects mostly adults, and women 50 years and older are six times as likely as men to develop rectal prolapse. While few men develop prolapse, those who do are much younger, averaging 40 years of age or less. In younger patients, there is higher rate of defecation disorders, autism, developmental delay, and psychiatric problems requiring multiple medications. Definitive treatment of rectal prolapse requires surgery.

CAUSES

While several factors are thought to be linked to rectal prolapse, there is no clear cut “cause.” An estimated 30% to 67% of patients have chronic constipation (infrequent stools or severe straining) and an additional 15% have diarrhea. In the past, this condition was assumed to be linked to giving birth multiple times by vaginal delivery. However, as many as 35% of patients with rectal prolapse never gave birth and it can occur in men. There might be some genetic predisposition to this condition; in other words: some patients are more prone based on their genes to develop this condition while others don’t.

SYMPTOMS

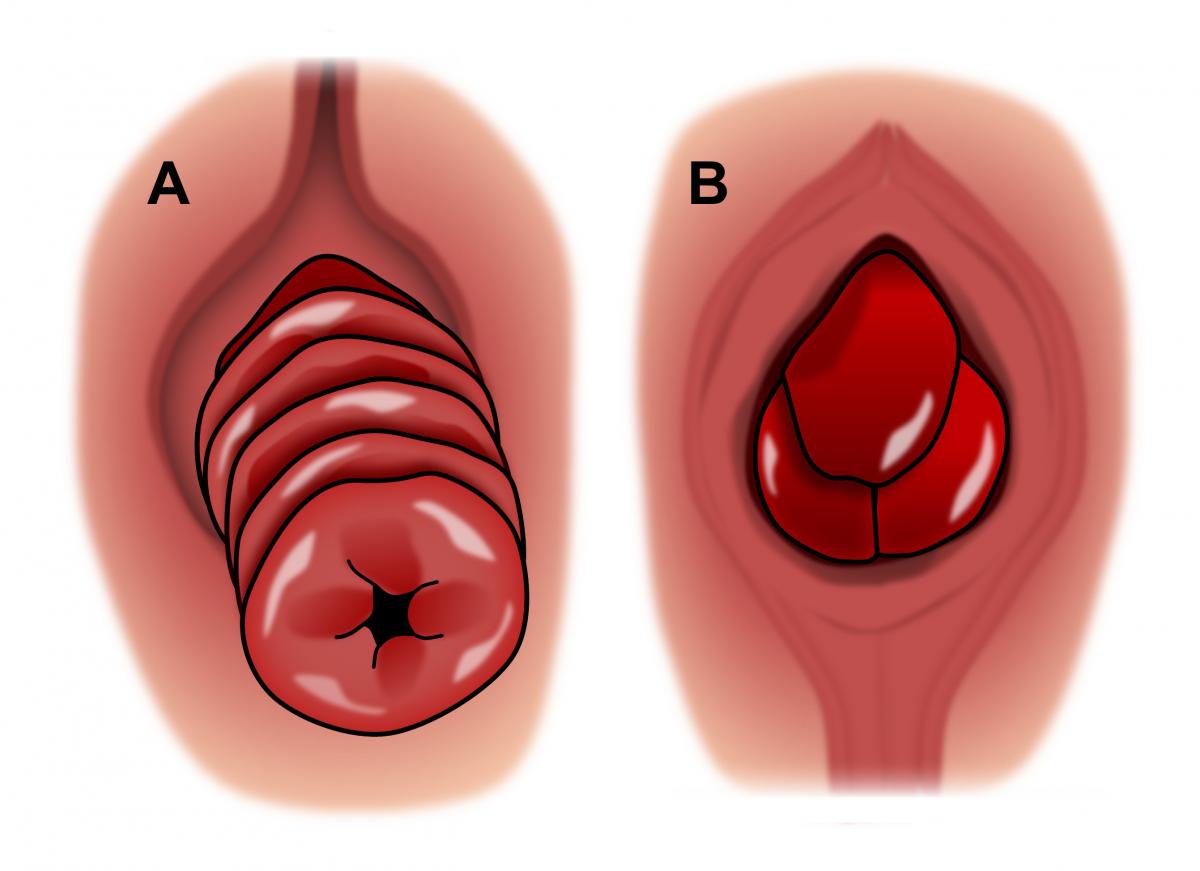

A common question is whether hemorrhoids and rectal prolapse are the same. Bleeding and/or tissue that protrudes from the rectum are common symptoms of both, but there is a major difference. Rectal prolapse involves an entire segment of the bowel located higher up within the body. Hemorrhoids involve only the inner layer of the bowel near the anal opening.

Rectal prolapse tends to develop gradually. Initially, the prolapse can come out after a bowel movement (BM), then return to its normal position. As the problem worsens, the protrusion may need to be pushed back in. For some people, it might stay outside and cause a sensation of “sitting on a ball.”

A = Rectal Prolapse

B = Hemorrhoids

About half of the patients with rectal prolapse may also have constipation. The prolapse itself can worsen constipation by blocking stool from passing easily. As the prolapse worsens, it may even contribute to fecal incontinence (not being able to fully control gas or bowel movements). It is not unusual for some patients to note bouts of both constipation and incontinence as well.

Over time, the lining of the protruding rectum may become thickened and inflamed, leading to seepage of fluid, mucus, and sometimes significant bleeding. The prolapsed tissue can become stuck or “incarcerated” outside of the anus. This can lead to a serious condition in which the circulation of blood to the rectum diminishes or even stops, requiring emergency surgery.

DIAGNOSIS

During the first visit, your colon and rectal surgeon will perform a thorough medical history and anorectal examination. The surgeon will likely ask about bowel habits, constipation, fecal incontinence, urinary symptoms or bulging sensations in the vagina or perineum.

The surgeon will examine the anorectal area. You may be asked to squeeze and relax the anal sphincter muscles while the doctor is palpating the anal canal. This helps the doctor get a sense of how well the anal sphincter is functioning.

If the prolapse is not visible while you are on the examination table, you may be asked to sit on a toilet and strain as if you are having a bowel movement. It is important for the surgeon to see the prolapsed tissue in order to distinguish between prolapsed hemorrhoids versus rectal prolapse, since the treatment of these conditions is very different. Some patients bring in photos of the prolapsed rectum which they have taken at home, since it may be uncomfortable or not possible to show the surgeon the extent or severity of the prolapse in an office setting.

In some cases, a rectal prolapse may be "hidden" or internal, making diagnosis more difficult. Your doctor may request additional testing for diagnosis. These may include:

- Defecography: This is a study in which the patient is given an enema to simulate having a bowel movement, and then pictures are taken using an X-ray or MRI machine. This shows the motion of the pelvic organs and muscles during a bowel movement. Defecography may also show other problems related to the pelvic floor. These should be addressed by a urogynecologist (a specialist of the urinary and reproductive organs) when planning the appropriate mode of treatment. Sometimes, fixing rectal prolapse can cause other pelvic floor problems to worsen if they are not simultaneously dealt with.

- Anorectal Manometry: A small probe is inserted into the rectum to test and measure muscle functions and reflexes of the pelvis, rectum and anus used during bowel movements.

- Colonic transit study (“Sitzmark” test): Patients with rectal prolapse in the setting of lifelong constipation may be asked to undergo a transit study to evaluate their colon’s ability to evacuate stool. This involves swallowing a capsule containing multiple markers that can be seen on an abdominal x-ray. Several x-rays are then taken over a five-day period to see how the markers move through the small intestine and colon, referred to as “transit time.” Patients found to have unusually long transit times may benefit from having some or, less likely all, of their colon removed at the time of the repair of their rectal prolapse.

- Colonoscopy: Colonoscopy is a procedure where a long, flexible, tubular instrument called a colonoscope is used to look at the entire inner lining of the colon (large intestine) and the rectum. This will often be necessary to rule out any associated polyps or cancer prior to treatment for rectal prolapse.

TREATMENT

If left untreated, rectal prolapse does not turn into cancer. But, the amount of prolapsing tissue will likely increase over time. Although constipation and straining play a role in this condition, correcting this may not improve an existing rectal prolapse. The prolapse events may occur more easily, such as with standing rather than just after having a BM. The risk of permanent or worsening fecal incontinence increases with time as well, due to stretching of the anal sphincter muscle and risk of nerve damage. The length of time that these changes will occur is widely variable and differs from person to person.

There are several methods used to surgically repair rectal prolapse. Generally speaking, rectal prolapse can be repaired either through the abdomen, or from the bottom (by operating on the perineal side). Options include removing part of the rectum, or pulling the rectum back up and anchoring it. Sometimes mesh is used to reinforce the rectum.

The optimal treatment depends on the size of the prolapse and the patient’s overall health. An abdominal approach offers the best chance for a long-term successful repair of rectal prolapse, provided the patient is medically fit for surgery. Operations from the perineal side are often reserved for elderly or frail patients, or those with very severe medical conditions that limit options for anesthesia during surgery.

ABDOMINAL APPROACHES

For rectal prolapse repair through the abdomen, the surgeon might make an incision in the lower abdomen, or use minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopy or robotic-assisted surgery. This entails placing a camera and surgical instruments through small incisions to perform the surgery, which is called a rectopexy.

The rectum is dissected free from the sides of the pelvis, pulled upwards, then secured to the sacrum (back wall of the pelvis). Depending on the surgeon’s preference, the rectum may be sutured directly to the sacrum with stitches or a prosthetic material (mesh) may be included. Regardless of the specific technique used, the intent is to hold the rectum in the appropriate position until the body heals and scar tissue forms, securing the rectum in place. Overall, the result of this approach is very good, with less than 10% of patients experiencing a return of the prolapse. For patients with a long history of constipation, the surgeon may recommend removal of a portion of the colon during this operation in order to improve their bowel function.

It is important to note that although the prolapse can be fixed, the function (incontinence or constipation) may not always improve. In a small number of cases, a potential complication of abdominal rectopexy is the development of new or worsened constipation. Following abdominal rectopexy, 15% of patients will develop constipation for the first time and at least half of those who were constipated prior to surgery are made worse. Fiber, fluids, and stool softeners may be needed to ease constipation following rectal prolapse repairs of any type. Occasionally, mild laxatives may be needed temporarily after surgery. Sexual dysfunction may be reported in some patients following the extensive pelvic dissection involved in this surgery.

PERINEAL APPROACHES

The choice to undergo a perineal approach to repair of rectal prolapse depends upon a number of factors, but these patients tend to be older, with more serious medical problems, or are undergoing emergency surgery for incarcerated prolapse (where the rectum is “stuck” on the outside) with worsening damage to the rectum.

The most common perineal approach is the perineal rectosigmoidectomy or “Altemeier” procedure, named after the surgeon who popularized this operation. During surgery, the prolapsed rectum is pulled down and out of the body, then removed. The remaining colon is then sewn or stapled to the anus. This surgery can be performed without general anesthesia and it is associated with less post-operative pain and a shorter hospital stay. However, the risk of recurrence can be as high as up to 30%.

Complications include bleeding, infection, or leakage of stool through the reconnected area and into the pelvis. Some patients experience worsening fecal incontinence afterward, so some surgeons recommend tightening the pelvic floor muscles with sutures (levatoroplasty) at the time of this surgery.

A less commonly performed perineal procedure is the mucosal sleeve resection (“Delorme” procedure). Rather than remove the prolapsing rectum, the inner lining of the rectum is stripped away and then the muscles of the rectum are folded and sewn onto themselves to reduce the prolapse. This particular procedure may be recommended in the setting of a small prolapse, or if the prolapse involves part, but not all, of the circumference of the rectum. Incontinence is improved in 40-50% of patients after this procedure. The recurrence rate is generally quoted as 10-15%, which is higher than the abdominal approaches.Complications specific to the Delorme procedure included bleeding, leakage of the sewn connection, and narrowing of the anal opening (stricture). Prolapse can return in up to 26% of patients, and is generally felt to be higher than with perineal rectosigmoidectomy.

PROGNOSIS

For a large majority of patients, surgery relieves or greatly improves symptoms. Prolapse or some other condition may have weakened the anal sphincter muscles. However, these muscles have the potential to regain strength after the prolapse has been corrected.

Factors that influence outcome after surgery include the condition of the anal sphincter muscles before surgery, whether the prolapse is internal (intussusception) or external, the length of time that the patient has experienced symptoms, and the overall health of the patient. It may take as long as one year to determine the impact of surgery on bowel function. Chronic constipation and straining after surgical correction should be avoided.

WHAT IS A COLON AND RECTAL SURGEON?

Colon and rectal surgeons are experts in the surgical and non-surgical treatment of diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. They have completed advanced surgical training in the treatment of these diseases as well as full general surgical training. Board-certified colon and rectal surgeons complete residencies in general surgery and colon and rectal surgery, and pass intensive examinations conducted by the American board of Surgery and the American Board of Colon and Rectal Surgery. They are well-versed in the treatment of both benign and malignant diseases of the colon, rectum and anus and are able to perform routine screening examinations and surgically treat conditions if indicated to do so.

DISCLAIMER

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is dedicated to ensuring high-quality patient care by advancing the science, prevention and management of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum and anus. These brochures are inclusive but not prescriptive. Their purpose is to provide information on diseases and processes, rather than dictate a specific form of treatment. They are intended for the use of all practitioners, health care workers and patients who desire information about the management of the conditions addressed. It should be recognized that these brochures should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of methods of care reasonably directed to obtain the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure must be made by the physician in light of all the circumstances presented by the individual patient.

ASCRS committee members review and update information for accuracy. We believe content is medically accurate at the time it was produced.

CITATIONS

Gurland B, Zutshi M. Chapter 60, “Rectal Prolapse”. Chapter in Steele SR, Hull TL, Read TE, Saclarides TJ, Senagore AJ, Whitlow CB, Eds. The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery, 3rd edition. Springer, New York, NY; 2016.

Bordeianou L, Paquette I, Johnson E, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Rectal Prolapse. Dis Colon Rectum 2017;60(11):1121-1131

[[all pictures from ASCRS textbook chapter on rectal prolapse except for hemorrhoid picture, which is from previous version of the brochure]]